Below is Part II of an examination of the decades-long series of events, decisions, compromises and money-grabs that led to the end of college football as we know it. I strongly recommend reading Part I before continuing.

Obsession to Crown a Champion

Certainly, the aim of practically every college athletic squad is a championship but for college football that quest required the glorious winning of your bowl game. With the new system, bowl games seemed like they would be getting in the way of the new aim -- chasing an undisputed title and gaining the biggest payday along the way.

By 1990 there were nineteen bowl games and both schools and coaches considered it an honor to play in them. For players, your collegiate career simply wasn't complete unless you played in and won a bowl game. But as the nineties moved forward, with realignment taking place and big corporate dollars entering the game, the NCAA and college football's power brokers began to wonder if the bowl system had run its course. Football had long been the only college sport where the champion was not determined by some form of tournament or playoff. In addition, since 1968 (when the Associated Press began crowning a national champion) the two top-ranked teams had faced one other in a bowl game only six times. For a time, United Press International also crowned a champion -- sometimes a different one than the AP. In 1978, for example, USC and Alabama each won their bowl game and both finished with one loss. The result was a split national championship -- UPI selected USC and AP chose Alabama (despite the head-scratching fact that Alabama's lone loss was to USC.) Further complicating matters was that many conferences had contractual agreements with bowl committees that bound the conference champion to play in a specific bowl, regardless of any other circumstance. Thus, it was common for the two top-ranked teams at the end of the regular season to never have the opportunity to meet and decide a unanimous national champion. This obviously created lively debate in years where there was no consensus single best team in the land. The situation went on for decades until the early nineties when, after two straight years of controversy (1990 and 1991) the call for a #1 vs. #2 national championship game could, in the eyes of some, no longer be ignored.

College football began experimenting, first with a "Bowl Coalition" and then the "Bowl Alliance", whose rules and structure mandated a meeting between #1 and #2 to be contested in one of the major bowls. The Bowl Championship Series combined polls with computer rankings to determine the two best teams so they could be pitted against one another; the NCAA secured big dollars from sponsors and broadcasters for these games; and all of the top football schools in the country had dollar signs in their eyes more than ever. Unfortunately, there were two major problems with BCS. First, the computer rankings were both convoluted and often called into question. Second, because the goal now was to have a definitive determination after the end of the season rankings, it meant that bowl games would have to defer and forgo years of tradition so that teams that previously had been playing for berths in specific major bowls would now be free to play in others. For example, if the PAC 12 champion was one of the top two teams, it wouldn't necessarily be playing the Big 10 champion in the Rose Bowl, as had always been the case. Similarly, the SEC winner was no longer bound to the Sugar Bowl. Other traditional tie-ins were also affected and the free for all that resulted became yet another indicator of how unmanageable college football was becoming. Certainly, the aim of practically every athletic squad is a championship but for college football that quest required the glorious winning of your bowl game. With the new system, bowl games seemed like they would be getting in the way of the new aim -- chasing an undisputed title and gaining the biggest payday along the way.

A series of selection controversies ensued and itsoon became apparent that the BCS was fundamentally flawed.

- In 2001, Oregon, ranked second in the AP poll, was bypassed for the championship game in favor of Nebraska -- despite Nebraska's 62-36 blowout loss to Colorado in its final regular season game.

- In 2003, three BCS Automatic Qualifying (AQ) conference teams (LSU, Oklahoma and USC) finished the regular season with one loss. Three (Non-AQ) conference teams also finished with one loss (TCU, Boise State and Miami of Ohio) sparking the argument that the BCS was unfair to Non-AQ conference teams. LSU beat Oklahoma in the BCS Championship game and USC beat Michigan in the Rose Bowl and ended up No. 1 in the final AP poll, resulting in yet another split national championship.

- In 2008, Utah was excluded from the BCS championship (despite being the only undefeated Division 1 team) and finished second in the final AP poll behind Florida.

- In 2009, five schools finished the regular season undefeated: Alabama, Texas, Cincinnati, TCU, and Boise State. The BCS formula selected traditional powers Alabama and Texas as the top two teams, which again fueled cries of bias toward the traditional powers.

- In 2010, three teams -- Oregon, Auburn, and TCU -- all finished the year with undefeated records. While TCU statistically led the other two teams in all three major phases of the game (1st in defense, 14th in offense and 13th in special teams) Oregon and Auburn were selected for the national title game.

Clearly the BCS was just as controversial and no better than the polls previously used to determine a champion. The call for some sort of playoff format grew increasingly louder. But a playoff wouldn't be easy to execute. Football wouldn't be able to mimic the NCAA basketball tournament where teams play every other day. Football players needed recovery time, so unless teams were willing to play into late January and February, anything other than a four team playoff would be unfeasible. So that's where things landed. Today we essentially have a four team football championship tournament with (presumably) the four highest ranked teams in the final regular season poll as the participants.

I say "presumably" because the selection committee, as it did this past season, is free to choose whomever they deem to be the four best teams, regardless of their record, if they won their conference championship, or any other factors. So this entire system solves nothing. The four teams selected continue to be second guessed the same way they were when the national champion was subjectively named subsequent to the bowl games. We witnessed this just this past season when Florida State was left out of the top four despite being undefeated and winning its conference. This type of controversy led the NCAA to expand the playoff to 12 teams beginning with the 2024 season. But of course this won't solve anything either, as the teams that finish 13th, 14th, 15th, etc., will almost always have a case for why they should have been chosen over another program. The expansion also serves to further diminish the prestige and tradition of the bowl games, essentially making them simply the venues or "containers" for the series of playoff games.

Moreover, with the bowl games so devalued, players have begun sitting out. Many of them no doubt question why they should play in something like the Duke's Mayo Bowl when it means risking injury and jeopardizing a fat pro contract. Not long ago, passing on your bowl game would have been unheard of but in the 2003, University of Miami running back Willis McGahee took a brutal hit in the Fiesta Bowl that destroyed his left knee. McGahee was a Heisman finalist and top pro prospect expected to go in the top five of the NFL draft -- but after the injury his stock fell and he wasn't selected until the 23rd pick.

Jaylon Smith's story is similar. The former Notre Dame linebacker was projected as a top pick in the 2016 draft before tearing ligaments in his knee and sustaining nerve damage during the Fiesta Bowl. This led to a steep fall in Smith's draft stock -- one that cost him an estimated $10-$20 million.

Smith's and McGahee's stories became cautionary tales for players. With bowl games now having no real significance unless they are part of the college football playoff, top players today often opt out of their bowl games and begin preparing for the draft. (Christian McCaffrey, Bradley Chubb, Anthony Richardson, Kenny Pickett, Breece Hall and this year's number one pick Caleb Williams are good examples,)

Defiance and Concessions

The tide of public sentiment, pushback, criticism from every direction, and now lawsuits have become too much for the NCAA to navigate and still operate as an effective governing body.

Over the last few decades, America has become increasingly (dare I say excessively) litigious. Didn't get into the college of your choice?.. File a lawsuit claiming discrimination... Don't like the state telling you to close your business during the pandemic?... Take it to court... Madonna concert started two hours late?... Sue her.

It's emblematic of what our nation has become -- unwilling to do the hard things and unaccepting of circumstances and judgments that don't go in our favor. It's famously said the the U.S. is a nation of laws... but that only works when its citizenry recognizes and submits to some type of authority. This doesn't mean we should all swallow whatever the powers that be hand out. Certainly there are injustices we suffer and manifestations of idiocracy that are foisted upon us. It's right to challenge things like this. But the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction and we've lost our sense of being members of a society. Every single thing that goes against us is now falsely labeled as being an infringement on our civil rights.

The NCAA serves as a organization that regulates student athletics for over a thousand member schools and close to half a million student athletes. But the NCAA can only accomplish this when its constituents operate under -- and yes, submit -- to the NCAA's rulings. Somewhere along the way, it became the norm to not only criticize the NCAA but also question its authority to prescribe the guidelines and regulations to which its member schools must adhere.

As a result, we've seen an abundance of federal (and even Supreme Court) cases targeting the NCAA -- challenges to rulings on player eligibility, appeals for reversal of sanctions levied for recruiting violations, and more. This past season was a great example. The University of Michigan, after preliminary investigation by the Big Ten conference, was deemed to have violated an NCAA rule that prohibits off-campus, in-person scouting of future opponents. Allegedly, this was part of an elaborate scheme to steal opponents' signs. As a penalty, Michigan head coach Jim Harbaugh (who had run afoul of the NCAA more than once prior) was suspended for three games. What was Michigan's response? After penning a letter that first contested Big Ten commissioner Tony Petitti's jurisdiction in punishing the program, the school issued a lengthy statement that condemned the conference (and the NCAA) for rushing to judgment before a full investigation could be completed. Significantly, no where along the line did Harbaugh or anyone else connected with the school expressly deny that cheating had taken place -- the video evidence of Wolverines off-field analyst Connor Stallions clearly visible on the sideline at a Central Michigan game was too damning for that. Yet that didn't stop Michigan heading further down the legal path and securing a temporary restraining order against Harbaugh's suspension.

Again, governing bodies -- in any sector of society but particularly sports leagues --- can only operate effectively when those governed willingly abide. This is how societies and other entities are able to function. We all agree to pull our cars to the side of the road to let an ambulance go by. We all stand in line and wait our turn at the post office. We all accept the determinations of our teachers as they dole out grades on our math tests. In each of these instances, there's agreement to stipulate to the judgement a higher authority. But the grievance and litigiousness that now permeates American society in general has made its way into college football:

Coach got suspended for stealing signs?... Find a judge to issue a stay... NCAA penalized your school for recruiting violations?... File a lawsuit... Star wide out got ruled ineligible?... Rip the NCAA in the media and conduct a public relations war until they cave.

What makes this even worse is the indignance that often accompanies it. ESPN commentator (and Michigan alumnus) Desmond Howard came to Harbaugh's defense. Eleven members of the Michigan House of Representatives penned a letter to the Big Ten expressing outrage. Still, what we didn't hear from either of those parties was a flat out denial or even a plausible explanation for the preponderance of video and other evidence against Stallions and the Michigan program. At no point was anyone at Michigan willing to own up to what most deemed obvious. Instead, the conference and the NCAA got slammed for supposedly denying due process. It was a very Trumpian response, in that the perpetrator of wrongdoings turns to legal challenges, injunctions, claims of unfair treatment and delay tactics. In Michigan's case, it seems to have worked. The NCAA agreed to drop its investigation of Harbaugh; he served his three game wrist slap suspension and the team went on to make the college playoff and win the national title. Now, with Harbaugh having left the university for the greener pastures of the NFL, the entire matter will likely be forgotten, even though its entirely likely that what transpired is grounds for Michigan's championship to be vacated.

It's all because the tide of public sentiment, pushback, criticism from every direction, and now lawsuits have become too much for the NCAA to navigate and still serve as an effective body. The association has lost significant portions of its respect and its power in recent year and has acquiesced to this pressure by changing many of its most longstanding and necessary rules... even those critical to maintaining fairness, parity, and competitive balance in the sport. Which brings me to the final factor that has led to the degradation of college football.

The transfer portal

Prior to the NCAA's rule change, very few transfers would have been permissible without the player having to sit out a year. Today these kinds of ridiculous musical chairs scenarios are happening en masse across the NCAA each and every season.

Facing a tidal wave of negative press, rebellion in the ranks and what seemed like an endless string of lawsuits, the NCAA's capitulation continued. Cries of hypocrisy were launched, this time against the rules surrounding the eligibility of transfer athletes.

The transfer portal launched in the fall of 2018, so it's not as new as many believe. It was implemented to bring more order and process to the mechanics of student athletes seeking to change schools. Windows were established where players could formally enter the portal, schools and coaches could view statuses, and player compliance to all requirements needed to transfer could be tracked. But in 2021, due to the disintegrating power of the NCAA, it once again made concessions to longstanding policies and ratified a new rule that allowed athletes in all sports to transfer without sitting out a year. (Previously, with regard to the five traditional “revenue sports”, upon transferring, players were required to sit out for a season before they were eligible -- except in instances where the athlete was moving from FBS to FCS, or unless they were granted a special waiver.) This concession pleased players and most of the NCAA's critics who were failing to understand (or didn't care) that the "sit out a year" rule was one of the last tools the NCAA had to prevent under the table payments that could entice players to leave one program in favor of another. It also was one of the only ways to dissuade them from leaving a school just to chase bigger and better NIL money.

The rule change effectively turned the transfer portal into, in the words of one NCAA official from the SEC, "chaos." Players today are transferring schools at an alarming rate simply because they believe they're not getting enough playing time... or because their position coach left... or because the team underperformed or isn't on TV enough. Take the case below.

In 2018, JT Daniels was the starting quarterback for USC. He played a year and then in the opening game of the 2019 season, tore his ACL Kedon Slovis became the new starter and played so well that rather than staying and trying to win his job back, Daniels decided to transfer Georgia. He was granted immediate eligibility to play and in 2020 he started four games and shared the position with Stetson Bennett that season. Then, in 2021 spotty play and injuries saw Daniels lose his job to Bennett so Daniels took advantage of the new NCAA transfer rule and switched schools again, this time moving to West Virginia for the 2022 season. Halfway through the year, he was benched and on Dec 5 of that year (you guessed it) Daniels entered the transfer portal a third time and wound up at Rice.

Meanwhile, back at USC, Jaxson Dart replaced Slovis who wasn't playing well. Slovis, having lost his starting job, transferred to Pitt. But the next off season USC hired Lincoln Riley as head coach and it was rumored that QB Caleb Williams, who played for Riley at Oklahoma, would follow Riley to LA so Dart entered the portal and transferred to Ole Miss. Williams departure from Oklahoma left the starting job there vacant and it could have been filled by Spencer Rattler, who was the starter prior to Williams... except as soon as Williams took Rattler's job the previous season, Rattler transferred to South Carolina... Chaos indeed.

Prior to the NCAA's rule change, very few transfers would have been permissible without the player having to sit out a year. Today these kinds of ridiculous musical chairs scenarios are happening en masse across the NCAA each and every season. A year ago, 456 scholarship players appeared in the portal on Day 1 and 780 total players from FBS, FCS and Division II went in. This non-stop program hopping severely injures the competitive balance of the sport, as high caliber players at every position now transfer at the mere hint of losing their starter status, to follow a coach, or for potentially larger NIL payments. The latter two almost certainly had a lot to do with the University of Colorado's 2023 season. New coach Deion Sanders brought in an astonishing 53 transfers -- that's close to half of the team's total roster. Sanders' celebrity, relatability to the modern athlete and the type of culture he fosters had a lot to do with this -- but so did NIL. Sanders had numerous endorsement deals in place long before he made it to in Colorado and upon his arrival his celebrity and star personality shined a spotlight on the program among sponsors and advertisers looking to attach their brand to a team that was increasingly gaining national attention. And as we know, more advertisers equal more NIL opportunity for players.

|

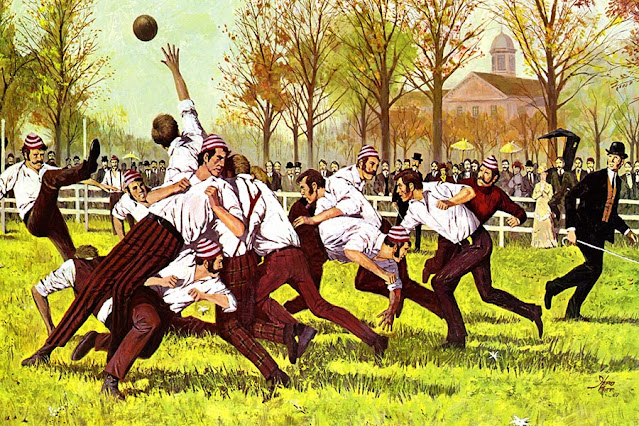

| Illustration of the very first college football game -- Princeton vs Rutgers, 1869 |

Thus we can all say goodbye to the game we once loved. America's second oldest team sport in fact, played since 1869. College football is more of a "showcase" now than a sport. It used to be the name on the front of the jersey that mattered -- now it's the name on the back. Players used to play for the honor of winning the PAC 12 championship, or Bedlam, or making the All-America team and being introduced on a Bob Hope Special. Now all of those things are extinct and players aspire to star in the next Dr. Pepper "Fansville" commercial. The NCAA, once a steadfast authority that oversaw all aspects of the game, is accused of being out of touch with the modern athlete and is now ridiculed by coaches and university presidents at every turn. No longer is there any allegiance to conference or to school. Those things are mere niceties best left to us simple, naive and wistfully nostalgic fans.

So long college football. We'll miss you.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment