The Michigan Wolverines just defeated the Washington Huskies to win the college football national championship. The victory put a cap on the 2023 college football season but in many ways it also marks the end of 155 years of the country's second oldest organized sport. The events of the last several years, the choices of university officials, rulings by judges, and other factors have finally brought college football to a tipping point where it seems the sport's most defining rules, guidelines and provisions have been compromised (or altogether eliminated) to the point where college football no longer resembles the sport it once was. NCAA football has become the wild west -- complete with rustlers, guns for hire, and more opportunists and villains than it can handle it seems. Here are all the things that slowly killed the college game.

The demise of college football began with the creeping hand of corporate influence and

the money grabbing that ensued. Beginning

in the early 1990's, the sports world was seduced by the

lure of the big dollars of Fortune 500 and other large companies. The 80's had seen Nike, Adidas, Gatorade and other brands strike deals with college and pro-level teams to provide shoes, apparel and more. These, plus endorsement deals with the decade's individual superstars, including Michael Jordan, Wayne Gretzky and Bo Jackson, had proved tremendously lucrative. As

the US economy began roaring under the Clinton administration, and the birth of the internet led to the rise of wealthy tech

companies like AOL, Yahoo and Cisco, these

companies began looking for ways to elevate their brands and increase public

awareness. The tens of millions of viewers watching sporting

events each week provided the huge audiences they were

looking to reach.

From

the earliest days of baseball -- America's oldest professional sport -- billboards for beer and cigarette brands were a regular site at ballparks and stadiums. Soon after, play-by-play announcers for baseball, football,

basketball and boxing began interrupting their calls to offer a word

from the sponsor, whether it was a breakfast cereal, shaving cream,

or clothing brand. Later, with the advent of television, games were

brought to you by local and national companies in industries including hardware, automobiles, hair care and insurance. But this advertising was always in the

background -- fairly innocuous and far from anything one would consider obnoxious. But as time changed, businesses

of the new economy wanted a bigger bang for the their buck than

billboards or live reads could offer. No longer would companies be satisfied with signage inside the stadium. Instead they sought a much higher profile by acquiring naming rights for the stadiums and arenas where teams played. So it was that by the mid-90's corporate sponsorship in sports reached new heights as American sports stadiums and ballparks quickly sold out (no pun intended.) In 1995, Candlestick Park became 3 Com Park, after the manufacturer of networking equipment. In 1996, the newly opening Pac Bell Park would debut. The following year, Jack Murphy Stadium, home of the NFL's San Diego Chargers became Qualcomm Stadium. We also got Coors Field, Invesco Stadium and several others. From coast to coast, our most famous sports venues were unceremoniously rebranded as big corps shelled out millions to have their names attached to sports franchises.

The Death of the Bowl Games

Around the same time this was taking place, there was also a major disruption in the college bowl system. Bowl games had been played since since 1902 and more were gradually added each decade beginning in the 1930's. By the eighties, the corporate giants (with their footprint now clearly established in the NFL) turned to the college game. Thanks to its new, deep pocketed sponsor, the Sugar Bowl became known officially as the "USF&G Sugar Bowl" in 1988. The next year, the Orange Bowl became the "Fedex Orange Bowl." All of the other bowls followed suit and this soon led to an unwieldy increase in the number of bowl games. To this point, bowl games were events rich in tradition and history. (The Sugar Bowl, for example, has been played since 1935 and came about because Louisiana was once the nation's leading producer of sugar. The game's solid silver trophy was made in London in 1830 during the reign of King George IV and was gifted to the bowl's organizers for the inaugural game.) After corporate sponsorship creeped in, history and tradition were swept aside and bowl names were shamelessly bastardized to afford the sponsor top billing in all press materials and during the TV broadcast.

The final step in this grand sell out was to create all new bowl games -- because after all, more bowls meant more money for everyone. It didn't take long for things to get completely out of hand in this regard evidenced by the fact that several of the newer bowl games have no other name other than that of the sponsor itself. Thus we've seen the likes of the Meineke Car Care Bowl, Little Caesar's Pizza Bowl, GoDaddy.com Bowl, and (God help us) the Pop Tarts Bowl, just to name a few.

Compensation and NIL Concerns

While big businesses were scrambling to stake claim of sports venues, and Nike was profiting and building its brand through partnerships with the professional athletes, new opinions began to form regarding compensation for college athletes. For instance, while practically every other nation on the globe sent players from their professional leagues to compete in the Olympics in sports like basketball, and volleyball, the U.S. had long maintained that only amateur athletes should be eligible for the Olympic Games. This was in spite of the fact that track, cycling and other American sports clubs had long been subsidizing its athletes training costs and even paying them stipends -- something that for all intents and purposes amounted to professionalism. But during the late 80's, the International and United States Olympic Committees began relaxing its rules and by 1992 professionals (including the famous "Dream Team") were ruled eligible in practically every Olympic sport. The line between professionals and amateurs became further blurred.

For decades, the goal for top high school football players was to gain a scholarship to a top university, excel there, graduate, get drafted and then make all your money in the NFL. Sure, there were unscrupulous backroom deals being made. Various NCAA investigations would reveal that money, cars and other enticements were offered to recruits to sign with a certain school and boosters or "friends of the program" provided cash payments and bonuses for outstanding play. Still, the fundamental tenet remained intact -- paying college players was illegal. Yet there was a growing sentiment that athletes were somehow being exploited. Many reasoned that the hundreds of millions the NCAA's member schools were making from TV rights were gained off of the backs of poor student-athletes. Others pointed to the fat multi-year contracts top coaches were signing. And while it was true that most top players were being paid in the form of full scholarships (a single year's tuition, room and board at major universities like Stanford, Michigan or Duke costs around $60,000 for example) such arguments held little sway. Figures like these seemed a mere pittance compared to the millions the schools were making, Thus, the opinion that college athletes should be paid continued into the 2000's.

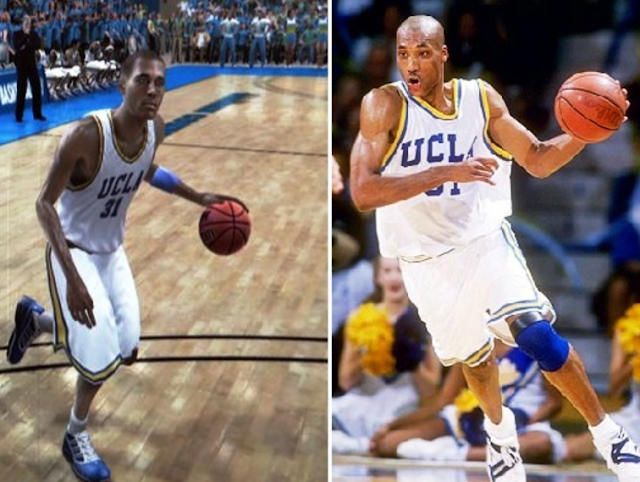

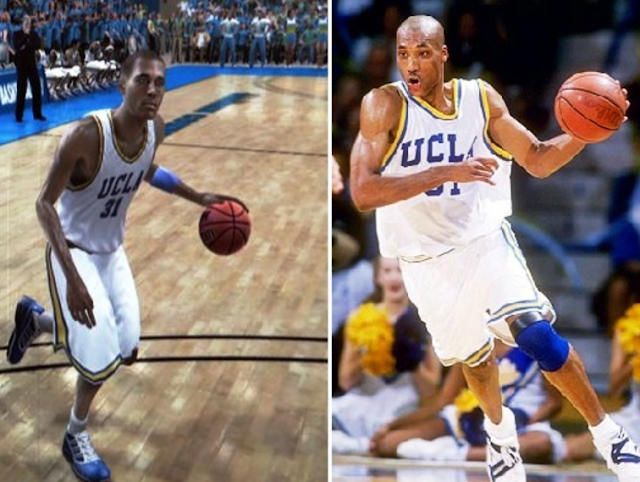

Then in 2009, former basketball star Ed O'Bannon, who had led the UCLA Bruins to a national title in 1995, filed a class action against the NCAA to challenge its rules regarding the use of players' likenesses. Among other things, the O'Bannon case argued that the restrictions on compensation for the use of athletes' names, images and likenesses (NIL) for video games, live game telecasts, and other purposes violated antitrust laws. O'Bannon brought the suit after learning that his (and scores of other former players') likenesses were being used in

EA Sports NCAA Basketball video games without the players' consent. EA Sports had established a licensing agreement with the NCAA but the individuals players were all left out, making the hypocrisy clear -- others could profit off of the performance and fame of college athletes but not the the athletes themselves.

O'Bannon eventually won the case and EA soon abandoned both its NCAA football and basketball games. Similar lawsuits followed and the courts continued to side against the NCAA. Now, not only was public sentiment seemingly in favor of rewriting compensation rules for college players but so was the legal system. The NCAA was clearly losing its grip as judges (who previously considered college athletics completely subject to NCAA regulations) now felt compelled to step in and overrule longstanding policies.

So the NCAA read the writing on the wall and finally began to seriously consider ways in which players might be compensated. Unfortunately, paying players is a lot easier said than done. Initially, ideas revolved around only paying athletes in the "revenue generating sports" ((baseball, men’s and women’s basketball, football and men’s ice hockey.) It's easy to see how this idea might have quickly been dismissed. First there was the matter of equity. Should the third string safety be paid the same as a Heisman candidate running back?... You can also imagine it wouldn't have been long before someone brought a lawsuit claiming only paying the revenue generating sports teams was discriminatory. And then of course there was

Title 9. If you're paying the men's teams and not the women's it was a super safe bet there'd be all kinds of additional lawsuits quickly filed.

It's possible though that the NCAA never even seriously considered all this because the decision was more or less taken out of the their hands. In 2019, California passed the

“Fair Pay to Play Act” -- which was the first state NIL law enacted. The legislation basically set the bar for how college athletes could be compensated moving forward. Players could now to be paid based on their value as an individual. More simply, any player could accept any endorsement deal, appearance fee or other payment available to them in the free market (provided it didn't create a conflict of interest with a deal already signed by the player's school.) The NCAA called the legislation harmful and "an existential threat to college sports" and even toyed with the idea of declaring all NCAA players in states who allowed payments ineligible. But threats don't get much emptier than that. It didn't take long for the association to capitulate to the new paradigm.

Conference realignment

Further disruption came to the NCAA's status quo with regard to its member conferences. Since their inception, conference affiliations had been both voluntary and fluid. Technically, institutions were free to switch conferences whenever they wished, so long as they gave notice and paid any agreed upon exit or entrance fees. Despite this, more often than not, a sense of logic prevailed and teams by and large remained in conferences that corresponded with their location on the map. That all changed in the nineties when football powerhouses Penn State and Florida State joined the Big 10 and ACC respectively. Meanwhile, the Big East looked to replicate its success as a basketball conference by adding five football schools. Notre Dame, which had always been staunchly independent, began flirting with the idea of joining the Big 10 and the Southwest Conference disintegrated altogether, its member teams joining the WAC, Conference USA and the Big 8 (which subsequently became the Big 12.) Tradition was once again pushed aside and nonsensical realignments (like Miami joining the Big East) proved that what mattered most now were the financials and what a conference could offer its member schools in terms of TV revenue.

No comments:

Post a Comment